How the green Echo Parakeet was saved from extinction

Saving the Echo Parakeet

Back in the mid-1980s things had reached crisis point for the world’s rarest parrot. By 1986 only ten or so Echo parakeets were left in the wild, of which only three were female. It was considered one of the most endangered species on earth.

Today, we have the Government of Mauritius, via the Forestry service and NPCS (National Parks & Conservation Service) to thank for its survival, with the support of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, the World Parrot Trust and the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation. Along with other endangered birds like the pink pigeon and Mauritius kestrel, the emerald green Echo parakeet is one of only a handful of bird species endemic to Mauritius, and its journey from the brink of extinction to a small but steadily growing population is one of the most remarkable conservation success stories of recent years.

How did it get so bad?

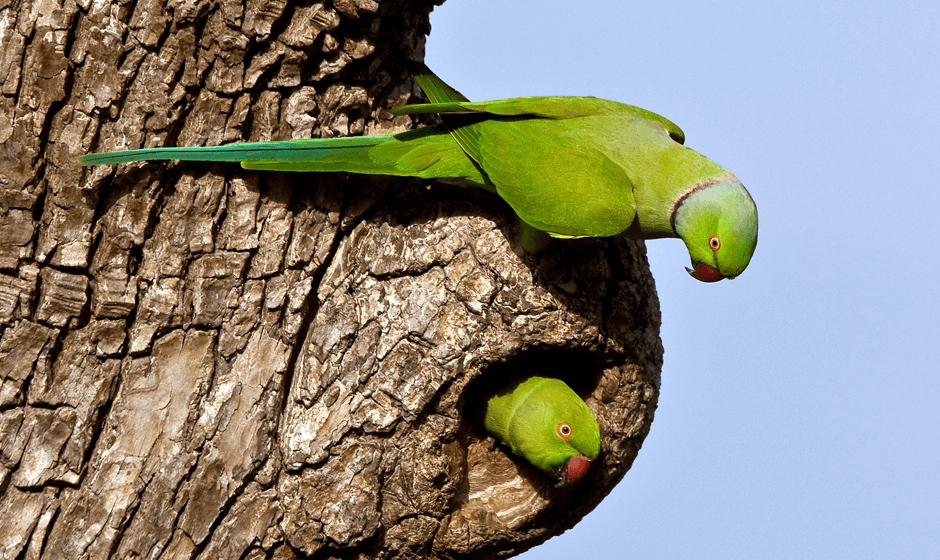

The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust had been working since the mid-1970s to help save the endangered birds of Mauritius, but were battling a number of challenging conditions. The remaining parakeets were struggling to find suitable trees to nest in, after much of their limited native habitat was compromised by invasive species and eroded by humans, deer and wild pigs – and the few nests that did remain were raided by introduced predators like the black rat.

This lack of nesting sites caused breeding to plummet, and on top of this they were faced with competition from the ubiquitous Afro-Asian Rose-ringed parakeet; a parrot which was probably brought to Mauritius by Indian indentured labourers, though of course, the importance of native biodiversity and invasive species were unknown at that time. In fact, in that era exotic plants and animals that could boost food production were considered valuable. Nevertheless, this particular parrot was extraordinarily adept at living in habitats disturbed by deforestation and urbanisation. This situation forced the final few birds into other types of habitat that were unable to support their needs and left them vulnerable to outbreaks of disease.

Not yet as dead as a dodo

But the last remaining birds were still clinging on, and that was enough for the Mauritian government, whose spirit of conservation and strong commitment to saving endangered species provided a boost to other committed organisations, scientists, and volunteers – all of whom were determined not to let the Echo parakeet go the same way as the most infamous Mauritian bird of all, the dodo.

A concerted conservation effort set out to prove that the Echo parakeet was still a viable species, and government plans to provide feeding stations, restore natural habitat and plant native trees were put into action, at considerable cost. The researchers at Durrell – who’d already managed to increase the numbers of the endemic Mauritius kestrel and pink pigeon – adapted the previously successful method of removing hatchlings from their nests, to reduce squab mortality and create a better chance of survival in the face of natural food shortages.

Once reared, these captive-bred Echo parakeets were released and monitored in artificial nest boxes, and then captive-bred chicks were gradually introduced alongside. The mechanism for rebuilding a viable species was in place.

Challenges ahead

Today, the Echo parakeet flies freely in a slither of native forest less than 40km2 within Black River Gorges National Park, and the species has been downgraded from Critically Endangered to Endangered. The number of parakeets living in the wild stands at around 500-600 – still an alarmingly low figure, but a shining example of how the collaborative work of NPCS and other organisations has brought a species teetering on the edge of survival back from the brink.

Efforts are now focused on managing the threat of parrot beak and feather disease (PBFD); a potentially fatal virus which causes progressive damage to the beak and feathers, and the continued monitoring of breeding programmes and habitat suitability, to ensure every bird is given the greatest possible chance to survive.

To find out more, visit the Durrell.org blog for recent news from Echo parakeet conservationists in the field.